What it means to be a brother

The birth order of brothers, says George Howe Colt, is just one of the things that cause them to be so different.

History is full of brothers so different that it seems impossible they could have the same parents.

A brief sampling through the ages might include the Arouets (Armand was a sanctimonious, evangelical Catholic; his younger brother Frangois-Marie, better known by his pen name, Voltaire, was a witty, irreverent satirist and a savage critic of the Catholic Church); the Melvilles (Gansevoort became a dutiful, responsible lawyer; his younger brother Herman became a world traveler and iconoclastic writer known to his family as “the runaway brother”); and the Carters (sober and pious Jimmy became president; his younger brother, Billy, played the court jester and drunken buffoon).

How can siblings, who share so much genetically and environmentally, be so different? For many years, social scientists assumed that a family affects the children within it almost identically, and that siblings, raised under the same roof by the same parents, tend to be far more similar than not. But over the past three decades, studies of intelligence, personality, interests, attitudes, and psychopathology have concluded that siblings raised in the same family are, in fact, almost as different from each other as unrelated people raised in separate families.

The answer to sibling difference is, in part, genetic. Biological siblings share, on average, half their genes; if personality traits were entirely genetic, siblings would be 50 percent similar as well as 50 percent different—even before factoring in the effects of being raised in the same family by the same parents. But biological siblings have personality correlations of about 15 percent. (Even identical twins have only about a 50 percent overlap.) Although siblings share about half of each other’s genes, not only is the genetic contribution of each parent halved, but the sequence of those shared genes is rearranged through a process called recombination. The behavioral geneticist David Lykken has observed that, genetically speaking, siblings are like people who receive telephone numbers with the same digits arranged in a different sequence. Just as those telephone numbers, when dialed, will result in entirely different connections, genes that have been scrambled will express themselves in widely different personalities.

But this is only part of the puzzle. A growing amount of research suggests that siblings may be influenced most strongly by the things they don’t share: birth order, age, friends, teachers, and the vagaries of chance. And they don’t even really share the things they appear to have in common—if not identical genes, then seemingly identical parents, homes, and often schools—because each of them perceives those things differently. Psychologists say that the experience of each child within a family is so distinct that each grows up in his own unique “micro-environment.” In effect, each sibling grows up in a different family.

The notion that parents should treat their children equally is relatively new. And treating each child according to his or her needs is natural and unavoidable. A restive infant demands more attention than one who sleeps through the night, a rambunctious toddler more than her independent 6-year-old brother, a sick child more than a healthy one. But the line between differential and preferential treatment can be thin. Even the most well-meaning, Spock-indoctrinated parent may be unconsciously drawn to the child who is higher achieving, less demand- ing, or more affectionate. The way a parent reacts to a child depends, of course, on that parent’s own upbringing and temperament. This may also depend on whether the pregnancy was wanted or unwanted, planned or unplanned. After the birth of their first child, John Cheever’s aging, quarrelsome parents had no desire to have a second, a fact they went out of their way to let him know. “If I hadn’t drunk two manhat-tans one afternoon,” his mother told him, “you never would have been conceived.” Cheever’s parents treated their second-born as little more than an appendage to their beloved first, which surely contributed to his lifelong need to be desired. As a friend observed after Cheever’s death, “If there’s someone who never loved himself, it was John.”

Anecdotal evidence suggests that favoritism can have enduring consequences. “A man who has been the indisputable favorite of his mother keeps for life the feeling of a conqueror, that confidence of success that often induces real success,” wrote Freud, whose parents treated him like a hothouse flower at the expense of his six younger siblings, cultivating a sense of entitlement that he would flex for the rest of his life. (Freud, whose mother called him “My golden Sigi,” didn’t bother to discuss the effects of favoritism on the non-favored child.)

Being the parental favorite, however, may be a mixed blessing. The preferred child may earn the envy or even the enmity of his siblings. He may grow up assuming that the world owes him a living. A Hong Kong study found a higher incidence of low self esteem and suicidal ideation in adolescents who believed their parents played favorites. Surprisingly, the higher rate held true for both the favored and the non-favored child.

IN A 1937 paper, the psychologist Alfred Adler suggested that birth order has psychological ramifications as well.

Adler declared that the firstborn child, having been “dethroned” by the arrival of a brother or sister, struggles to maintain his dominant status and is likely to become a kind of surrogate parent who cleaves to law and order. The second-born child, said Adler, “behaves as if he were in a race, as if some one were a step or two in front and he had to hurry to get ahead of him. He is under full steam all the time. He trains continually to surpass his older brother and conquer him.” Unthreatened by the possibility of dethronement, the last-born tends to be spoiled; overshadowed by elder siblings, however, he may develop an inferiority complex. In keeping with the truism that psychologists tend to devise theories that reflect their personal circumstances, Adler was a second-born who struggled all his life to surpass his elder brother.

Subsequent research has refined and expanded on Adler’s observations. Born into a hothouse environment in which they enjoy undivided parental attention, firstborns tend to be precocious achievers. They walk and talk earlier than later-borns. They have higher IQs—three points higher, on average, than that of their next eldest sibling, according to a 2007 study. They have been described as assertive, ambitious, conscientious, responsible, organized, and self-reliant. Not only scientists but American presidents, British prime ministers, members of Congress, Rhodes scholars, Ivy League students, Nobel Prize winners, MBAs, CEOs, surgeons, pilots, and professors are more likely to be firstborns. Of the first 23 American astronauts in space, 21 were firstborns and the other two were only children—only children being considered by birth-order theorists to be a kind of iiber-eldest.

Firstborn sons are encouraged to be role models. They are expected to act as substitute parents. “You must not reckon yourself only their brother,” the Prince of Wales told the 10-year-old future King George III in 1749, “but I hope you will be a kind father to them.’’(George tried, but his eight siblings, an unusually profligate and promiscuous lot, proved to be no less difficult to control than the 13 colonies.) They are expected to be babysitters, nursemaids, and nannies. Benjamin Spock, who grew up feeding, changing, and rocking to sleep his five younger siblings, would, as the author of best-selling baby-care books, become pediatrician-parent to a nation.

The second-born child, unable to compete physically with his larger, stronger brother, learns to work things out with words. Second-borns tend to be mediators, compromisers, peacemakers. They are often described as cooperative, sociable, empathetic, flexible, agreeable. Second-borns

may also become fiercely competitive as they struggle to keep pace with their older siblings. Yet the second-born sibling may feel that no matter what he does, his older brother has done it before him. Henry James wrote that his brother William “had gained such an advance of me in his 16 months’ experience of the world before mine began that I never for all the time of childhood and youth in the least caught up with him or overtook him.” The second-born’s sense of being second best may be reinforced by parents (the Duchess of Marlborough famously referred to her two sons as “the heir and the spare”).

* ■ 1h Ts

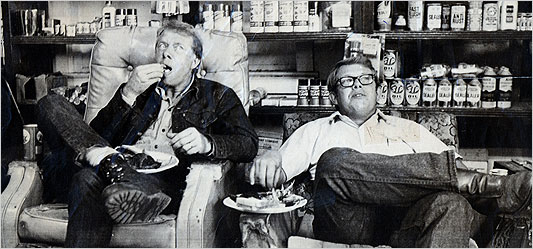

Last-borns like Steven Colbert are often pranksters.

If firstborns often are the achievers and middle children the peacemakers, last-borns are the entertainers and spotlight-seekers. Some of history’s greatest satirists—Swift, Voltaire, Franklin, Twain—were born at or near the tail end of large families, and many of their spiritual heirs, 20th-century comedians like Charlie Chaplin, Oliver Hardy, Danny Kaye, Mel Brooks, Jim Carrey,

Eddie Murphy, and Steve Martin, are last-borns. (Stephen Colbert is the eleventh of eleven.) Last-borns are also more likely to be pranksters and risk-takers; they are overrepresented among the ranks of explorers, entrepreneurs, firemen, and fighter pilots. Last-borns are said to be charming, affectionate, spontaneous, mischievous, and— because the baby of the family tends to get infantilized—pampered, temperamental, irresponsible, and manipulative.

1HE 19TH-CENTURY POLYMATH Francis Galton championed the importance of heredity in shaping one’s life, but he also noted that “the whimsical effects of chance” often play a vital role. Siblings may share family milestones—a move, parental job loss, parental depression, the illness or death of a parent—but they may experience them very differently, according to personality or developmental stage.

For John Adams’s three sons, timing was everything. In 1778, when Adams was appointed by Congress to argue the American cause in Europe, he took along 10-year-old John Quincy. Too young for the journey, 7-year-old Charles and 5-year-old Thomas remained with their mother, Abigail, on the family farm. John Quincy would spend seven years abroad with his father, traveling from capital to capital; hobnobbing with Jefferson, Franklin, Lafayette, and a host of European intellectuals; serving, at the age of 14, as secretary to the American envoy in St. Petersburg; taking five-mile walks each morning before work with his father, who was grooming the child he called “the joy of my heart” for greatness. Meanwhile, his younger brothers worked at their lessons, did their chores, and submitted to their domineering mother. When Abigail joined her husband and eldest son in Europe, leaving her younger sons in her sister’s care, Charles and Thomas went entirely parentless for two years.

Given such curricula vitae, it was, perhaps, not surprising that John Quincy Adams became, among other things, a U.S. senator, Harvard professor^ minister to Great Britain, secretary of state, and president. Or that genial but feckless Charles spent more time drinking than studying at college, struggled to establish a law practice, squandered the $2,000 his older brother left him in trust, abandoned his wife and two small daughters, and died, alcoholic and broke, at the age of 30. Or that Thomas, unable to sustain a legal practice, served a year in the state legislature before quitting abruptly to become a drinker and gambler who failed to provide for his wife and seven children. Described by a nephew as “one of the most unpleasant characters in this world,” Thomas died, also alcoholic and broke, at the age of 59.

From Brothers by George Howe Colt.

©2012 by George Howe Colt.

Print

Print